u bassu, which follows it, accompanies it and supports it;

a terza, the highest tone, which enriches the chant, adding ornamental notes.

|

The themes of the Corsican songThe main themes are:

|

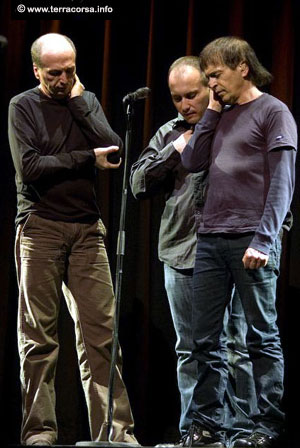

Traditionally, polyphony is sung by three men. Nowadays, women also sing polyphony (e.g. Isulatine, Jacky Micaelli). The singers form a circle, their arms

often placed on the shoulder of the neighbour. The hand on the ear has several reasons, the main one being to close the ear to avoid hearing the other voices

and to hear better one's own voice.

The paghjella is performed by accompanied soloists, like Ghjuvan Paulu Poletti, Antone Ciosi, Petru Guelfucci.

Many of the polyphonic songs have an oral tradition and were never noted.

Sometimes a monodic song becomes a Paghjella. During the Victoire de la Musique in 1995 the disc “Tribbiera” by Petru Guerfucci won the award for the best album of the year in the section Traditional Music.

Guelfucci describes that the titllesong “Tribbiera” was originally a monodic song, but he arranged it for polyphonic singing.

His idea to do this was that he wanted the music itself to convey the idea of working together.

The paghjella is performed by accompanied soloists, like Ghjuvan Paulu Poletti, Antone Ciosi, Petru Guelfucci.

Many of the polyphonic songs have an oral tradition and were never noted.

Sometimes a monodic song becomes a Paghjella. During the Victoire de la Musique in 1995 the disc “Tribbiera” by Petru Guerfucci won the award for the best album of the year in the section Traditional Music.

Guelfucci describes that the titllesong “Tribbiera” was originally a monodic song, but he arranged it for polyphonic singing.

His idea to do this was that he wanted the music itself to convey the idea of working together.

Many Corsican groups now enjoy big fame, also beyond the bounderies of Corsica: I Muvrini, A Filetta, Barbara Furtuna, Voci di Corsica, Les Nouvelles Polyphonies Corses,

Soledonna, I Chjami Aghjalesi, Isulatine, Tavagna, Caramusa.

The Corsican polyphony includes sacred and secular forms. Secular polyphony includes forms such as paghjella, terzetti, madrigale, lamentu and nanne.

Sacred polyphony is sometimes used in the Catholic mass and there are many traditional polyphonic mass chants. At concerts, the Miserere or the Kyrie

are frequently sung. Some more examples of the sacred polyphonic chant, also taken from the Mass, are Agnus Dei, Gloria, and Sanctus. O Salutaris,

and 'Diu vi salve Regina' (a hymn to the Virgin Mary and the national anthem) are other examples.

The case of the Chjami è Rispondi is also very original. This improvised poetic joust requires from

the performers a exceptional virtuosity. It often tells of daily events, can be very humourous and remains

very prized by the public.

We can still attend it in Casamaccioli in the Niolo , during the A SANTA DI NIOLU fair in the month of september.

We can still attend it in Casamaccioli in the Niolo , during the A SANTA DI NIOLU fair in the month of september.

Chjami è Rispondi

The Riacquistu

In the 1960s traditional Corsican music seemed doomed to fade away. The 1970s however, brought revival and retraditionalization not only in Corsica, but

throughout Europe. In Corsica, the riacquistu was closely allied to the nationalist movement. The youth of Corsica felt a sort of renewal in the air,

the spirit of Dylan's 'Blowing in the wind'. Lots of young men and women, studying or making a living for themselves at the continent, decided to

return to Corsica, and became active in the revivalist movement.

Traditional instruments | ||

|

Cetera Under the heading of the research linked to music, it is interesting to notice the success of certain undertakings of restoration of traditional instruments among those the Cetera, one of the most remarkable.

This traditional Corsican sistrum with 8 double choires, whose origin probably dates from the italian Middle-Ages, has been remade

by stringed-instrument makers, from the rare preserved models. This instrument is integrated with harmony to

ancient orchestra and it sometimes offers original tones to contemporary productions.

Well known instrument makers, who are building beautiful instruments, are

Christian Magdeleine (Bastia)

and Ugo Casalonga (Pigna).

Cialambella |

Le joueur de cetera (le forgeron Francescu Luigi Succi, 1850-1934) |

|

Pirula A flute made of reed, according with the theme of the Lamenti Pivana A flute made of goat horn |

|

| Le Cantu in paghjella profane et liturgique de Corse de tradition orale La paghjella est une tradition de chants corses interprétés par les hommes. Elle associe trois registres vocaux qui interviennent

toujours dans le même ordre : la segonda, qui commence, donne le ton et chante la mélodie principale ; lu bassu, qui suit, laccompagne et

le soutient ; et enfin la terza, qui a la voix la plus haute, enrichit le chant. La Paghjella fait un large usage de lécho et se chante a

capella dans diverses langues parmi lesquelles le corse, le sarde, le latin et le grec. Tradition orale à la fois profane et liturgique,

elle est chantée en différentes occasions festives, sociales et religieuses : au bar ou sur la place du village, lors des messes ou des

processions et lors des foires agricoles. Le principal mode de transmission est oral, principalement par lobservation et lécoute,

limitation et limmersion, dabord lors des offices liturgiques quotidiens auxquels assistent les jeunes garçons, puis à l'adolescence

au sein de la chorale paroissiale locale. Malgré les efforts des praticiens pour réactiver le répertoire, la paghjella a

progressivement perdu de sa vitalité du fait du déclin brutal de la transmission intergénérationnelle due à lémigration des

jeunes et de lappauvrissement du répertoire qui en a résulté. Si aucune mesure nest prise, la paghjella cessera dexister sous

sa forme actuelle, survivant uniquement comme produit touristique dépourvu des liens avec la communauté qui lui donnent son sens véritable.

|

| top | home |